Born to communist parents in Budapest where her father was studying medicine, Maysaloun grew up in Dir Hanna, a village in the North of Israel.

After a Masters in History of the Middle East at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Maysaloun’s interest shifted towards cinema. In 2012, she graduated from the Minshar School of Art in Tel Aviv. She has been living and working in Jaffa for the past nine years.

From 2010 to 2013, Maysaloun was in charge of communications at the Tel Aviv based NGO SADAKA, which promotes political and social change.

Since 2009, she is a member of the group PALESTINEMA, a group of young filmmakers whose objective is to promote Arab culture by organising screenings of films in Israel and Palestine

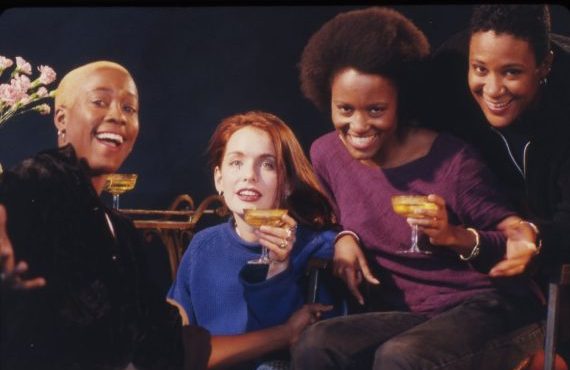

Maysaloun Hamoud -photo by Anne Maniglier

Maysaloun Hamoud in conversation with Haggai Matar – +972 Magazine

Is Tel Aviv the condition for freedom? Could this happen elsewhere, or is the Jewish hegemony in which the story is set needed for the girls’ feminist liberation?

“The movie takes place in Tel Aviv, because I wanted the imagery to be within a hegemonic space, but the scene in which they live is in Jaffa. The essence of the scene is Jaffa-Tel Aviv, and the plot-lines draw a lot of inspiration from what happens around me and from real characters in my own life…

Tel Aviv is a city, and that’s what a city does. It challenges. The same things would likely happen in Beirut or Amman…Tel Aviv is not the Berlin of the Middle East. It’s just the city that’s here. The scene here is unique because it’s Jewish-Arab, with a lot of mutual influence. Most young Palestinians in the city believe in a shared life, while the Jews [in this particular community] are left-wing and anti-Zionist, which is like a glue that creates mixed couples.”

The difference between religion and the religious

… “The atmosphere of the Arab Spring didn’t skip Palestine/Israel, we were all with them in spirit — in the opposition to oppression, patriarchy, chauvinism and the perpetuation of the old system. This generation can no longer continue playing around with obsolete codes. We have to put everything on the table, because as long as we keep sweeping our fears under the carpet, the carpet will rise and we will stumble. Fundamentalism is a serious disease, and if we don’t shake out the carpet it’s likely going to be too late.”

Now that the film has been commercially released, what response are you expecting to these sentiments, which are also at the heart of the movie?

“Some people will want to hang us in the town square, for sure. The conservatives. The film does something very clever: I don’t say a single bad thing about religion. Everyone has his own faith. That’s not what the religious say, but even among them there are no ‘bad guys.’ There are characters you fall in love with in conservative society as well. Nour wears a hijab; she isn’t leaving the faith. Yes, she’s searching for a place of liberation in her own world — the religious, believing world — and that’s the place I’m searching for. So I’m very curious as to what the religious will pick up from the film.

The film doesn’t let liberals off the hook. It holds up a mirror to them too. We all know those families, Christian or Muslim, that are terribly open, but in moments of truth everyone falls in line behind the same traditions. It’s not just Nour’s family from Umm al-Fahm — it’s also that of Salma, the Christian. And the film doesn’t go easy on Jews, either. Maybe they’ll say, ‘Hey, it happens among us too, how great,’ but they need to address the fact that they always leave Arabs out. It’s a case of not here, not there. But the essence [of the film] is the intra-Palestinian conversation.”

Drugs and alcohol are a significant part of the film — marijuana, MDMA and more. What does that mean to you?

“First of all, during the first party in the film they’re taking Ritalin, and that’s intentional, because the parents watching the movie are themselves giving their kids Ritalin. Coke generates more antagonism, so I didn’t put an emphasis on it.

But there’s more to say beyond that. We want to say that the current period is like the Sixties of the Arab world, and in an underground which you don’t want in the Middle East, everyone is taking every drug. It’s integral to the scene, and it influences identity, politics and culture. If we’re already doing it, why not show it?”

Balls in the face of BDS [The Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement works to end international support for Israel’s oppression of Palestinians and pressure Israel to comply with international law.]

Success aside, In Between also sheds light on the complications of politics and identity faced by many Palestinian citizens of Israel who are filmmakers. For example, Hamoud put together a soundtrack featuring original music by artists from different countries in the region, whose names she could not publish and who couldn’t be credited in the movie. The movie also features music by DAM, a Palestinian hip-hop group from Lod, who wrote a dance song especially for the film. “They were amazing collaborators and I love them so much,” Hamoud says.

Other artists who saw earlier versions of the movie wanted to collaborate, but ultimately felt that their reputation would be in danger if they worked on a film funded by Israeli government institutions.

One day, Hamoud met a musician in Ramallah who was especially enthusiastic when he heard the movie’s plot and watched some of the rushes. “So I told him, yalla, we’ve put ourselves on the line for this movie, put yourselves on the line and say, ‘We’ll be the first people to look at the complexity, at the Palestinians who are inside [Israel – h.m.].’ But in the end they refused, despite knowing that they were contradicting themselves. There’s no link between the synchronization among us and the separation that reality has created.

“Yes, the state is giving me money, because I deserve to make films from the money I pay [in taxes]. I’m not ashamed, and I deserve even more. And still, I would have taken money from elsewhere in order to lift the cloud of a boycott, but there’s nowhere else. So I took from the state, and the film will be screened as an Israeli-French movie, despite it being mostly Arab-Palestinian.”

Bitter candy

“People in the Israeli cinema world have never worked with the Arab community. They don’t know what it is. Arabs don’t go to the movies much, because there aren’t cinemas in their communities, they watch Hollywood films at home and there are no local movies they want to see. Now all of a sudden they have a reason to go out, and we need to make use of this swell in order to bring other people into the industry.”

But the most important thing of all for Hamoud is her dream that her movie will open up a “new era of representation of women in Palestinian cinema, in which the woman is at the center and not behind the male character,” she says.

“In most Palestinian movies the political story dominates the plot, and so [women] are generally represented as victims. Even in my early movies [filmed when she was a student – h.m.] I told women’s stories via men’s heroics. The women I want to show are all around us but are invisible in the movies. Gender, activism and liberation from the patriarchy can be feminist, even if that word doesn’t necessarily define the women themselves. One way of telling this complex story of women, and the weighty issues that accompany it, was to wrap the whole tale in simple cinematic language, almost American. It’s also the women’s internal language in the film. They are burdened by the outside world, but they see themselves in the same image we are accustomed to seeing in the cinematic output of a liberated and vibrant society. The film’s producer, Shlomi Elkabetz, calls this “bitter candy” — something wrapped in flamboyance and beauty. You get into the film, and then get kicked in the stomach.”

Translated from Hebrew by Natasha Roth.