In the second part of our interview writer/director Jonas Carpignano talks about working with Scorsese, his young lead Pio Amato and the perils of shooting in The Ciambra.

A Ciambra clearly delineates the various tribes in Rosarno – the Italians, Romani and Africans – and shows how only Pio can move freely between them, which makes Pio’s relationship with Ayiva one of the hopeful elements in the film.

I fundamentally believe that besides the coercive political, economic and national structures, exposure to “foreign elements,” whether they be people, food, or music is the only way to dissolve the artificial boundaries between us. To me, Pio can move freely through the complex layers of his world because none of them are truly foreign to him. He has grown up in a Calabria that has now Africans, Bulgarians, Romanians, and so on. For him they are part of the social fabric of his world. That was not the case for the previous generation.

The same is true for Marta in Mediterranea. She doesn’t see Ayiva as an invader. For her, Ayiva is a worker like so many others. She didn’t know what Calabria was like before the arrival of the Africans. Both Pio and Marta see Ayiva as Ayiva. And while both films are realistic about the limits of this relationship, I think they both depict a path forward towards a more “integrated” Calabria.

Pio’s grandfather represents a way of life that has disappeared. There is a wonderful moment in the film in which Pio has a vision of his grandfather, what was the inspiration for this?

History has a certain weight. We like to contextualize ourselves and to feel that we are part of something larger than ourselves, that we have roots and that we are the continuation of something that has come before us. This is true, to varying degrees, for all of us, but it is especially relevant in the Ciambra. Yet, if you really think about it, our connection with the past is more abstract that we would like to think. I mean, we cannot physically occupy the past, we can never experience it for ourselves. The past is something that is constantly reimagined, often to justify who we are or who we would like to be.

How did producer Martin Scorsese get involved?

RT Features and Sikelia have created a fund to support first and second films. The producers at RT saw Mediterranea, they liked it, and they brought it to Martin and his producing partner Emma Tillinger Koskoff, who were immediately supportive and enthusiastic about the project.

The nature of making films in Gioia Tauro is such that everything outside feels very, very abstract compared to what is happening on the ground. I spent the last year knowing that Martin Scorsese was a producer of the film but it didn’t really sink in until we got to the editing process. I was lucky to have his notes on several versions of the cut, and his thoughts surely made an impact on the film. On a larger level, not only his work is massively influential, but his approach to and respect for the medium is what I particularly value.

What was the process for creating the look of the film? What were some of the challenges in filming where you did?

While the building blocks were similar to the process for Mediterrana (and the shorts), the overall picture was very different and that came from the different perspective that the film inhabits. I always believe the film itself should feel like the main character. In that vein, Mediterranea feels very fragmented and closed in. The visual grammar is designed to mirror Ayiva’s perspective: he only has a fractured understanding of his surroundings and therefore the film only presents a fractured portrait of the place. In A Chjana, Pio’s grasp of his surroundings is more assured and, even though we used the same type of camera moves and editing style, the perspective is much larger, more comprehensive.

Shooting in the Ciambra was the challenge. It’s impossible to fully articulate what the Ciambra is like, but from the film I think you get an idea. It is a wild and unruly place where anything that can happen will happen, often ten or fifteen times over. Luckily we knew this before going in, so we gave ourself time. We ended up shooting for 91 days.

Can you talk about the music? As always the score and the pop songs are on.

I love pop music. I got this question a lot while I was on the road with Mediterranea, and I’ll say now what I said then: pop music is the common denominator. No matter what language you speak, no matter where you are from, when the beat drops on a song that everyone knows, everyone is suddenly on the same wavelength. Everyone is moving to the same rhythm and I find that to be a major icebreaker when venturing into less familiar territories.

The film ends with a boy becoming a man, but not without a cost. Do you consider it an optimistic ending?

Optimistic? In my own life I tend to be a very optimistic person, but I try not to think about my films in terms of optimism or pessimism. In the end the goal is to give the viewer my take on what life is like where I live, and to leave them to decide for themselves how they feel about it. While my films are not “objective,” they don’t have a specific agenda, they are not a rallying cry for any specific cause. They are primarily designed to be character explorations. They are about characters who find themselves in conflicting and contradictory situations, who must try to cope with those situations as best as they can.

While this film touches on race relations, poverty, stereotyping, crime, etc., it is ultimately about Pio, about who he is and who I see him becoming. In life, I am optimistic about Pio. I love him very, very much and I appreciate who he is now and who he will become. At the same time I realise that every place imposes certain structures that are often hard to shed when you live within them.

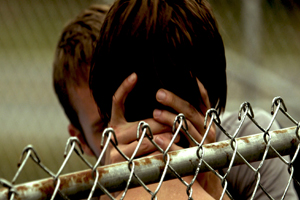

I think that if confronted with the choice he has to make in regard to Ayiva, Pio would do exactly what he did in the film. What happens is obviously very, very sad, but in the end I don’t think that the viewer will dislike him. Good people do bad things, and when our backs are against the wall we usually resort to tribalism and embrace the burden of identity, which is frequently the easy way out. People in the Ciambra have done all kinds of things that are viewed and judged as “bad,” but they are not bad people and I think this film is a testament to that.

So just like with the end of Mediterranea there are those who will view this ending optimistically and those who will view it pessimistically. In the end I think it’s important that, while Pio does what he does, we see how hard it is for him. It takes a toll on him, and ultimately if there is a path to some form of solidarity between the Africans and the Gypsies it will be through someone like Pio. You can be pessimistic about the social architecture imposed on Pio or you can be optimistic about seeing how he feels at home, and made to feel at home, in the African community. Nobody is perfect, and I am personally relieved to know that Pio Amato is out and about, doing his thing.

Find the first part of this interview on how Jonas met the Amato family on the Peccadillo Blog