THE WATERMELON WOMAN is a self-coined – Dunyementary – a fusion of fiction and documentary style filmmaking. In THE WATERMELON WOMAN, Cheryl Dunye uses investigative documentary shooting on video intercut with a formal fiction comedy drama structure shot on film. Inserted within the narrative is archive footage constructed by Dunye.

THE WATERMELON WOMAN is edutainment. We laugh while being educated about the erasure of Black women in cinematic history in general, and also the invisibility of Black lesbian actresses in Hollywood history. As we watch the film we begin to question what is real and what is fiction? THE WATERMELON WOMAN is the Black actress Fae Richards who had disappeared, undocumented in the mist of time.

The title “THE WATERMELON WOMAN” is a play on the association between racist depictions of Black people eating watermelons, equivalent to the often racist caricatured images of Black women as the Mammy/Maid characters in Hollywood. The title is also an homage to Melvin Van Peebles’ 1970 film WATERMELON MAN. Melvin Van Peebles is credited with starting the Blaxploitation era of cinema which heralded a new vision of modern African American cinema.

As THE WATERMELON WOMAN begins we see video footage of a white Jewish wedding with Black guests. As Cheryl, who is a wedding videographer sets up the frame, a white male photographer comes and tells the contributors to move around to suit his frame while she is shooting. She is of course outraged and tells him to wait his turn. This first scene sets the tone for the ways in which Black women’s stories are denied, overwritten or erased in Hollywood.

Cheryl in the film decides to search for the real Fae Richards. As she does so she interviews various gatekeepers of culture, who are unapologetic in their ignorance about Fae Richards. Lee Edwards, the Black gay man, played by Brian Freeman (Pomo Afro Homos – 1990–1995) is uninterested in anything to do with history of women in cinema, the CLIT archivist played by Sarah Schulman hoards Black womens’ archival assets and denies Cheryl access to the material, the cultural critic Camille Paglia played by herself, who while explaining the impact of the Mammy role, denies there is a racist element to them, and even posits the roles as empowering because she insists on viewing them through her own Italian American experience.

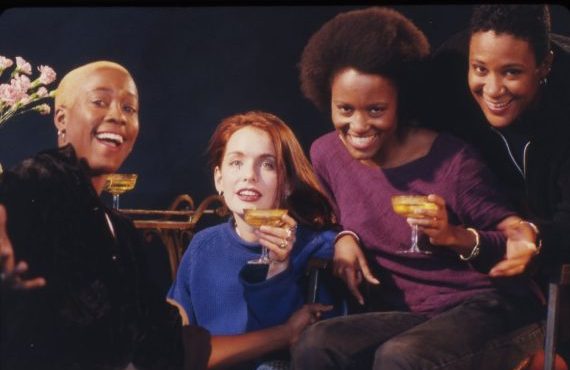

The complicity of white women in power structures is further reinforced when we learn that Fae Richards was in a lesbian relationship with a white film director Martha Paige who cast her in the Mammy roles. Martha Paige did nothing to write and direct roles for Fae that were outside of the Mammy/Maid roles. She instead built her reputation as a film director off plantation type dramas. In fact it is often Martha Paige who is referenced in the history books and not Fae Richards. Martha Paige is played by Alex Juhasz, one of the producers of THE WATERMELON WOMAN. Cheryl’s relationship with Diana played by Guinevere Turner (Go Fish, L Word, American Psycho, Notorious Bettie Page, Charlie Says) falls apart when Cheryl has the dawning realisation about her liberal white racist values and her attempted appropriation of Cheryl’s project.

At the same time Cheryl interviews older Black lesbians who let her know how much they revered Fae Richards, even as Hollywood rejected her, and dumped her when she got older. She uncovers Fae Richards rich and joyous life as a Black lesbian who was survived by June, her lover of 20 years. June is played by the iconic poet and essayist – Cheryl Clarke.

THE WATERMELON WOMAN is a genius film which subverts dominant cinema with a Black lesbian feminist aesthetic through centring dark-skinned Black women as characters and actors. And by placing Black masculine of centre women of various ages as objects of desire and love interests. Cheryl Dunye casts herself, a black lesbian woman, as the central character, a Black lesbian filmmaker called Cheryl in order to obtain authenticity in the role, as well as intrinsically preventing any erasure of Black lesbian desire or bodies.

THE WATERMELON WOMAN is a love letter to cinema – African American cinema in Philadelphia in particular, we learn about those film companies that existed in the 1930s and see the cinemas where African Americans watched the silver screen. THE WATERMELON WOMAN while exploring the invisibility of Black lesbian women in cinema, also creates its own queer archive. There are references to other queer works of art, the documentary elements allow for the use of actual LGBT people, Dunye uses music of Black lesbians like Toshi Reagon and if you check the credits you will see interns like Kimberly Peirce (Boys Don’t Cry, The L Word, Carrie ).

THE WATERMELON WOMAN tells us to speak to our queer elders and hear their stories in order to document histories/herstories/theirstories so we so we know they were there.

Campbell X